“Color” means “An appearance, semblance, or simulacrum, as distinguished from that which is real. A prima facia or apparent right. Hence, a deceptive appearance, a plausible, assumed exterior, concealing a lack of reality; a disguise or pretext. See also colorable.” Black’s Law Dictionary, 5th Edition, on page 240.

“Colorable” means “That which is in appearance only, and not in reality, what it purports to be, hence counterfeit feigned, having the appearance of truth.” Windle v. Flinn, 196 Or. 654, 251 P.2d 136, 146.

“Color of Law” means “The appearance or semblance, without the substance, of legal right. Misuse of power, possessed by virtue of state law and made possible only because wrongdoer is clothed with authority of state is action taken under ‘color of law.'” Atkins v. Lanning. D.C.Okl., 415 F. Supp. 186, 188.

If something is “color of law” then it is NOT law, it only looks like law. If you go to the website for the Office of Law Revision Counsel, you will see that most of the titles of the United States Code are “prima facia evidence of the laws of the United States”.

“prima facia” means “At first sight; on the first appearance; on the face of it; so far as can be judged from the first disclosure; presumably; a fact presumed to be true unless disproved by some evidence to the contrary.” State ex rel. Herbert v. Whims, 68 Ohio App. 39, 38 N.E.2d 596, 599, 22 O.O. 110. Black’s Law Dictionary 5th Edition page 1071.

Prima facia and color of law both go hand in hand, because if a law is prima facia evidence of the laws of the United States, that means it is color of law, by definition. In other words the bureaucrat presumes that the law applies to you until you defeat their presumption.

If you read these prima facia, color of law statutes, you will find them using words like “person”. I will use the color of law Title 26 USC as a typical way that they do it.

26 USC 7701 (a) (1) Person. The term “person†shall be construed to mean and include an individual, a trust, estate, partnership, association, company or corporation.

In the Internal Revenue code they say that a “person” has to pay taxes and obey their filing requirement etc., and most people think that they are such a “person”, so they do it, but there is a maxim of law that says something else.

Ejusdem Generis (eh-youse-dem generous) v adj. Latin for “of the same kind,” used to interpret loosely written statutes. Where a law lists specific classes of persons or things and then refers to them in general, the general statements only apply to the same kind of persons or things specifically listed. Example: if a law refers to automobiles, trucks, tractors, motorcycles and other motor-powered vehicles, “vehicles” would not include airplanes, since the list was of land-based transportation.

Pursuant to the Maxim of Law ejusdem generis the word “individual” is another type of fictitious entity because the rest of the entities are fictitious entities and in the rules of statutory construction, a definition must contain the same type of entities, or it is void for vagueness. Therefore, an “individual†and a “person” are different names for a corporation.

Title 15 USC Section 44 even provides for an “unincorporated corporation”.

When you do what a color of law statute says, you are deemed to have agreed to the terms of the contract, and ignorance of the law is not an excuse.

This is consistent with what the Courts are saying, a “Person” is:

a) “a variety of entities other than human beings.†Church of Scientology v U.S. Department of Justice, 612 F2d 417 (1979) at pg 418

b)  foreigners, not citizens….” United States v Otherson, 480 F. Supp. 1369 (1979) at pg 1373.

c) the words “person” and “whoever” include corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies…Title 1 U.S.C. Chapter 1 – Rules of Construction, Section 1

A sovereign is not a “person” in a legal sense and as far as a statute is concerned;

a) ” ‘in common usage, the term ‘person’ does not include the sovereign, [and] statutes employing the [word] are normally construed to exclude it.’ Wilson v Omaha Tribe, 442 US653 667, 61 L Ed 2d 153, 99 S Ct 2529 (1979) (quoting United States v Cooper Corp. 312 US 600, 604, 85 L Ed 1071, 61 S Ct 742 (1941). See also United States v Mine Workers, 330 US 258, 275, 91 L Ed 884, 67 S Ct 677 (1947)” Will v Michigan State Police, 491 US 58, 105 L. Ed. 2d 45, 109 S.Ct. 2304

b) “a sovereign is not a person in a legal sense†In re Fox, 52 N. Y. 535, 11 Am. Rep. 751; U.S. v. Fox, 94 U.S. 315, 24 L. Ed. 192

All of this is consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment because the Fourteenth Amendment talks about a “person” being a US citizen, and both of them are corporations.

Other terminologies which mean the same thing are “pretend legislation” and then it would also follow that offenses under “pretend legislation” would also be “pretend offenses”. These terminologies are found in the Declaration of Independence(1776).

For any statute to be legimate, there are certain requirements. For example, it has to have a preamble, it has to be approved by both the House of Representatives and the Senate, and signed by the President, and there are other requirements as well. The lack of any of these would make it color of law. Remember, “color of law” means it does NOT have authority, therefore, you have to agree with it, – it is a contract. That is why it is “prima facia”, which means it is “at first look”. In other words, at first look the courts presume that the statute affects you but if you can show that you didn’t agree to it in some way, then you are free to go.

Because the US Congress perjurers did their Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act, and also because state citizens are foreign to the United States, most people think that they have to go through a lot to prove that they did not agree to one of these so-called contracts, but the opposite is true.

Color of Law, and Prima Facia, and presumption are all associated with Admiralty Maritime Law courts.

Still don’t believe that the courts view these colorable codes, rules and regulations as a contract?

“The rights of the individuals are restricted only to the extent that they have been voluntarily surrendered by the citizenship to the agencies of government.”

City of Dallas v Mitchell, 245 S.W. 944

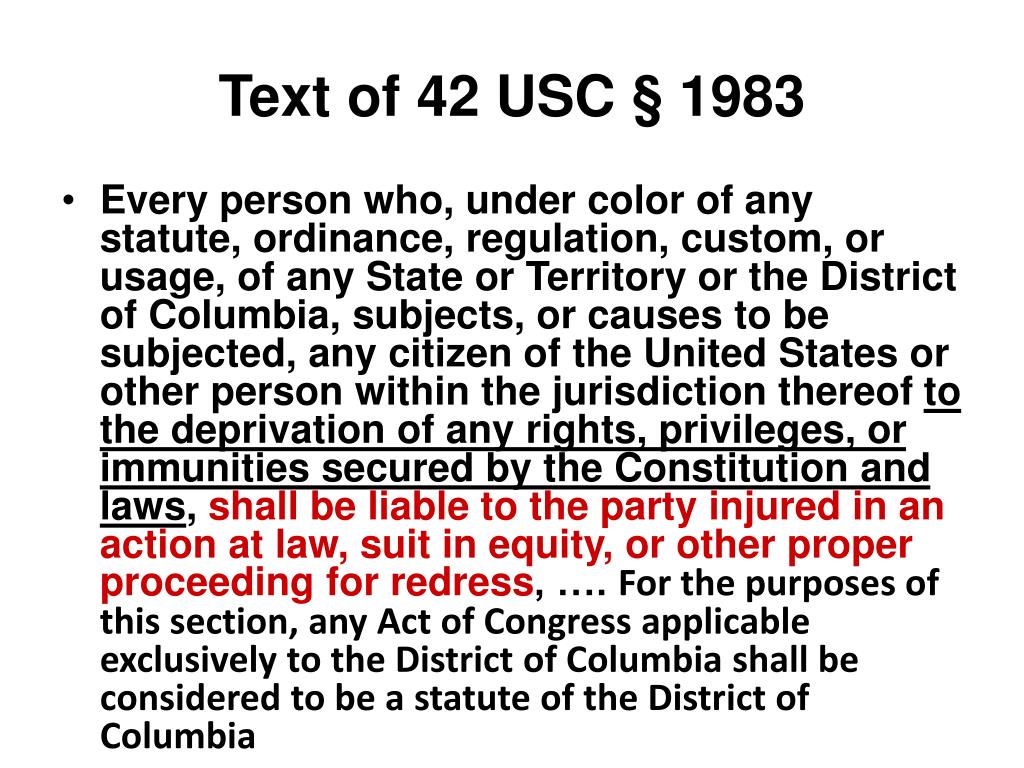

TITLE 18, U.S.C., SECTION 242

DEPRIVATION OF RIGHTS UNDER COLOR OF LAW

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States, … shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than one year, or both; and if bodily injury results from the acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts include the use, attempted use, or threatened use of a dangerous weapon, explosives, or fire, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and if death results from the acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts include kidnaping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill, shall be fined under this title, or imprisoned for any term of years or for life, or both, or may be sentenced to death.

This law further prohibits a person acting under color of law, statute, ordinance, regulation or custom to willfully subject or cause to be subjected any person to different punishments, pains, or penalties, than those prescribed for punishment of citizens on account of such person being an alien or by reason of his/her color or race.

Acts under “color of any law” include acts not only done by federal, state, or local officials within the bounds or limits of their lawful authority, but also acts done without and beyond the bounds of their lawful authority; provided that, in order for unlawful acts of any official to be done under “color of any law,” the unlawful acts must be done while such official is purporting or pretending to act in the performance of his/her official duties. This definition includes, in addition to law enforcement officials, individuals such as Mayors, Council persons, Judges, Nursing Home Proprietors, Security Guards, etc., persons who are bound by laws, statutes ordinances, or customs.

Title 42, U.S.C., Section 14141

Pattern and Practice

Title 42, U.S.C., Section 14141: makes it unlawful for state or local law enforcement agencies to allow officers to engage in a pattern or practice of conduct that deprives persons of rights protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States. This law is commonly referred to as the Police Misconduct Statute. This law gives DOJ the authority to seek civil remedies in cases where it is determined that law enforcement agencies have policies or practices which foster a pattern of misconduct by employees. This action is directed against an agency, not against individual officers. The types of issues which may initiate a Pattern and Practice investigation include:

1. Lack of supervision/monitoring of officers’ actions.

2. Officers not providing justification or reporting incidents involving the use of force.

3. Lack of, or improper training of officers.

4. A department having a citizen complaint process which treats complainants as adversaries.

Whenever the Attorney General has reasonable cause to believe that a violation has occurred, the Attorney General, for or in the name of the United States, may in a civil action obtain appropriate equitable and declaratory relief to eliminate the pattern or practice.

Types of misconduct covered include, among other things:

1. Excessive Force

2. Discriminatory Harassment

3. False Arrest

4. Coercive Sexual Conduct

5. Unlawful Stops, Searches, or Arrests

Title 18, U.S.C., Section 241

Conspiracy Against Rights

This statute makes it unlawful for two or more persons to conspire to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person of any state, territory or district in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him/her by the Constitution or the laws of the United States, (or because of his/her having exercised the same).

It further makes it unlawful for two or more persons to go in disguise on the highway or on the premises of another with the intent to prevent or hinder his/her free exercise or enjoyment of any rights so secured.

Punishment varies from a fine or imprisonment of up to ten years, or both; and if death results, or if such acts include kidnapping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned for any term of years, or for life, or may be sentenced to death.

It is a crime for one or more persons acting under color of law willfully to deprive or conspire to deprive another person of any right protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States. “Color of law” simply means that the person doing the act is using power given to him or her by a governmental agency (local, state or federal). Criminal acts under color of law include acts not only done by local, state, or federal officials within the bounds or limits of their lawful authority, but also acts done beyond the bounds of their lawful authority. Off-duty conduct may also be covered under color of law, if the perpetrator asserted their official status in some manner. Color of law may include public officials who are not law enforcement officers, for example, judges and prosecutors, as well as, in some circumstances, non governmental employees who are asserting state authority, such as private security guards. While the federal authority to investigate color of law type violations extends to any official acting under “color of law”, the vast majority of the allegations are against the law enforcement community. The average number of all federal civil rights cases initiated by the FBI from 1997 -2000 was 3513. Of those cases initiated, about 73% were allegations of color of law violations. Within the color of law allegations, about 82% were allegations of abuse of force with violence (59% of the total number of civil rights cases initiated).

Investigative Areas

Most of the FBI’s color of law investigations would fall into five broad areas:

1. excessive force;

2. sexual assaults;

3. false arrest/fabrication of evidence;

4. deprivation of property; and

5. failure to keep from harm.

In making arrests, maintaining order, and defending life, law enforcement officers are allowed to utilize whatever force is “reasonably” necessary. The breath and scope of the use of force is vast. The spectrum begins with the physical presence of the official through the utilization of deadly force. While some types of force used by law enforcement may be violent by their very nature, they may be considered “reasonable,” based upon the circumstances. However, violations of federal law occur where it can be shown that the force used was willfully “unreasonable” or “excessive” against individuals.

Sexual assaults by officials acting under “color of law” could happen in a variety of venues. They could occur in court scenarios, jails, and/or traffic stops to name just a few of the settings where an official might use their position of authority to coerce another individual into sexual compliance. The compliance is generally gained because of a threat of an official action against the other if they do not comply.

The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution guarantees the right against unreasonable searches or seizures. A law enforcement official using his authority provided under the “color of law” is allowed to stop individuals and even if necessary to search them and retain their property under certain circumstances. It is in the abuse of that discretionary power that a violation of a person’s civil rights might occur. An unlawful detention or an illegal confiscation of property would be examples of such an abuse of power.

An official would violate the color of law statute by fabricating evidence against or conducting a false arrest of an individual. That person’s rights of due process and unreasonable seizure have been violated. In the case of deprivation of property, the official would violate the color of law statute by unlawfully obtaining or maintaining the property of another. In that case, the official has overstepped or misapplied his authority.

The Fourteenth Amendment secures the right to due process and the Eighth Amendment also prohibits the use of cruel and unusual punishment. In an arrest or detention context, these rights would prohibit the use of force amounting to punishment (summary judgment). The idea being that a person accused of a crime is to be allowed the opportunity to have a trial and not be subjected to punishment without having been afforded the opportunity of the legal process.

The public entrusts its law enforcement officials with protecting the community. If it is shown that an official willfully failed to keep an individual from harm that official could be in violation of the color of law statute.

The Supreme Court has had to interpret the United States Constitution to construct law regulating the actions of those in the law enforcement community. Enforcement of these provisions does not require that any racial, religious, or other discriminatory motive existed.

Acting under color of [state] law is misuse of power, possessed by virtue of state law and made possible only because the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority of state law Thompson v. Zirkle, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 77654 (N.D. Ind. Oct. 17, 2007)

“The general rule is that an unconstitutional statute, though having the form and the name of law, is in reality no law, but is wholly void and ineffective for any purpose since unconstitutionality dates from the time of its enactment and not merely from the date of the decision so branding it; an unconstitutional law, in legal contemplation, is as inoperative as if it had never been passed … An unconstitutional law is void.â€

(16 Am. Jur. 2d, Sec. 178)

“An unconstitutional act is not law; it confers no rights; imposes no duties; affords no protection; it creates no office; it is in legal contemplation, as inoperative as it had never been passed.†Norton v. Shelby County.†118 U.S. 425

“If the State converts a liberty into a privilege, the citizen can engage in the right with impunity.†Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 373 US 262

“No State legislator or executive or judicial officer can war against the Constitution without violating his undertaking to support it.â€

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 78 S.Ct. 1401 (1958).

“The Constitution of these United States is the supreme law of the land. Any law that is repugnant to the Constitution is null and void of law.†Marbury v. Madison, 5 US 137

“No state shall convert a liberty into a privilege, license it, and attach a fee to it.†Murdock v. Penn., 319 US 105

“If the state converts a liberty into a privilege, the citizen can engage in the right with impunity.†Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 373 US 262

“Officers of the court have no immunity, when violating a Constitutional right, from liability. For they are deemed to know the law.†Owen v. Independence, 100 S.C.T. 1398, 445 US 622

“The court is to protect against any encroachment of Constitutionally secured liberties.†Boyd v. U.S., 116 U.S. 616

“State courts, like federal courts, have a “constitutional obligation†to safeguard personal liberties and to uphold federal law.†Stone v. Powell 428 US 465, 96 S. Ct. 3037, 49 L. Ed. 2d 1067.

“The obligation of state courts to give full effect to federal law is the same as that of federal courts.†New York v. Eno. 155 US 89, 15 S. Ct. 30, 39 L. Ed. 80.

“An administrative agency may not finally decide the limits of its statutory powers; this is a judicial function.†Social Security Board v. Nierotko. 327 US 358, 66 S. Ct. 637, 162 ALR 1445, 90 L. Ed. 719.

“State Police Power extends only to immediate threats to public safety, health, welfare, etc.,” Michigan v. Duke 266 US, 476 Led. At 449: which driving and speeding are not. California v. Farley Ced. Rpt. 89, 20 CA3d 1032 (1971):

“For a crime to exist, there must be an injured party (Corpus Delicti) There can be no sanction or penalty imposed on one because of this Constitutional right.” Sherer v. Cullen 481 F. 945:

“If any Tribunal (court) finds absence of proof of jurisdiction over a person and subject matter, the case must be dismissed.” Louisville v. Motley 2111 US 149, 29S. CT 42. “The Accuser Bears the Burden of Proof Beyond a Reasonable Doubtâ€.

Title 42 Penalties For Government Officers

The AUTHORITY FOR FINES (DAMAGES) CAUSED BY CRIMES BY GOVERNMENT OFFICERS.

These Damages were determined by GOVERNMENT itself for the violation listed.

Breach Penalty Authority

VIOLATION OF OATH OF OFFICE $250,000.00 18 USC 3571

DENIED PROPER WARRANT(S) $250,000.00 18 USC 3571

DENIED RIGHT OF REASONABLE

DEFENSE ARGUMENTS $250,000.00 18 USC 3571

DEFENSE EVIDENCE (RECORDS) $250,000.00 18 USC 357I

DENIED RIGHT TO TRUTH

IN EVIDENCE $250,000.00 18 USC 3571

SLAVERY (Forced Compliance

to contracts not held) $250,000.00 18 USC 3571

DENIED PROVISIONS IN THE

CONSTITUTION $250,000.00 18 USC 3571

TREASON (combined above actions). $250,000.00 18 USC 3571

GENOCIDE $1,000,000.00 18 USC 1091

MISPRISION OF FELONY $500.00 18 USC 4

CONSPIRACY $10,000.00 18 USC 241

EXTORTION $5,000.00 18 USC 872

MAIL THREATS $5,000.00 18 USC 876

FRAUD $10,000.00 18 USC 1001

FALSIFICATION OF DOCUMENTS $10,000.00 18 USC 1001

PERJURY $2,000.00 18 USC 1621

SUBORNATION OF PERJURY $2,000.00 18 USC 1622

GRAND THEFT (18 USC 2112) each $250,000.00

To determine multiply no. of counts by damage 18 USC 3571

RACKETEERING (Criminal) $25,000.00 18 USC 1963

RACKETEERING (Civil)

Wages Taken $x3 = 5? 18 USC 1964

(Sustained Damages [total] x 3)

Thirty-seven (37) Constitutional violations from Count 1: = $9,250,000.00 Damages Dealing with claims of “immunity.”

Any claim of ” immunity” is a fraud because, if valid, it would prevent removal from office for crimes against the people, which removal is authorized or even mandated under U.S. Constitution Article 2, Section IV; as well as 18 USC 241, 42 USC 1983, 1985, 1986, and other state Constitutions.

Precedents of Law established by COURT cases, which are in violation of law, render violations of law legally unassailable. Such a situation violates several specifically stated intents and purposes of the Constitution set forth in the Preamble; to establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, and secure the-blessings of liberty. This is for JUDGES, or anyone in any branch of government.

J.B.M.

a.) I can’t actually find in “SHUTTLESWORTH vs BIRMINGHAM” the Quote mentioned Above after reading thru it on Justia: AND there are two (2) “” Cases; one in 1963 and one in 1969! – which one is it, please…?!?

b.) I’m involved in a ‘Speeding’ Traffic Infraction [‘False Arrest,’ etc.!] in NYS and would like to know under Title 18 what would be the TOTAL Amount(s) of the Damage(s) to Sue them for; from the SPO, the Judge, the Mayor, the City, etc., for all of the ‘color of law’ Violations, under 42 USC Section 1983, please? – At least $1.75MM or more…?!? – jbm

Malika Duke

its Shuttleworth vs Birmingham Alabama. Easy to find and simple quick read! Consider taking our ticket terminator course! https://freedomfromgovernment.org/classes/

kbcole79

I’m just up reading and I am grateful that I found this community I’ve unlearned more than I have in my lifetime!