Just about 250 years ago, the great American democratic experiment began. Almost from the first day–and despite the contrary views of a succession of English monarchs–it assumed that an educated citizenry had no need of lawyers to write its laws or solve its disputes.

Lawyers were actually banned outright or faced tight restrictions in many colonies for much of the 18th century. Especially in Puritan New England, Quaker communities in Pennsylvania and Dutch settlements in New York, colonists firmly believed that disputes were best solved within the community, often by church-sponsored mediation.

The “Body of Liberties” adopted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1641 expressed the typical attitudes of the time:”Every man that findeth himselfe unfit to plead his own cause in any court shall have libertie to employ any man …, provided he give him noe fee or reward for his pain.”

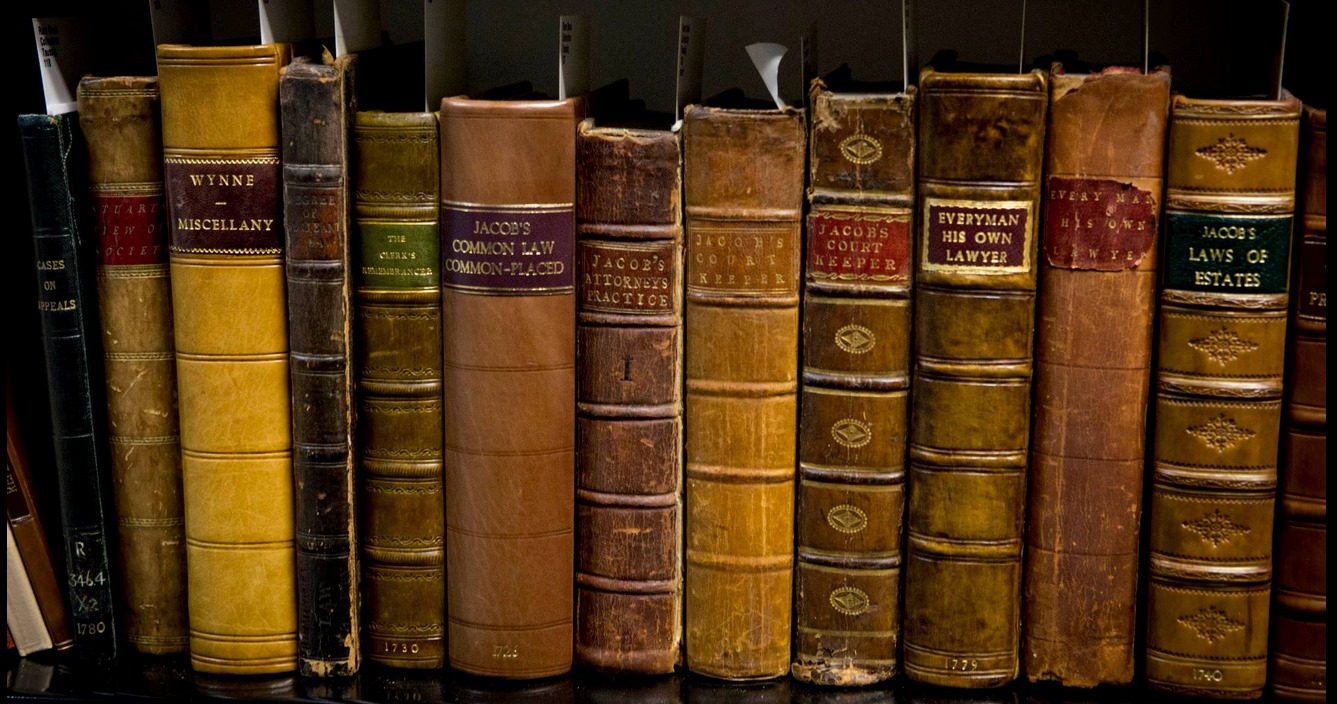

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, after English kings reasserted direct political authority over the colonies, England’s common law system–complete with courts, juries and lawyers–crossed the ocean. Even so, most citizens did not rely on lawyers for legal information. Historian Eldon Revere James found that between 1687 and 1788, not a single legal treatise intended for lawyers was published in America. During that period, all the legal treatises were for laymen.

One of the most popular self-help law books of the time, Every Man His Own Lawyer, published in London, was already in its ninth edition in 1784. Another, Every Man His Own Attorney, by Thomas Wooler (1845), which apparently was widely and effectively used for many years, contains a lament that could have been penned yesterday:”Much has been recently done, to simplify … practice in the courts; something has been gained in point of expedition; but little, if anything, in the reduction of the expense … Useless proceedings are still required, apparently for no other purpose than to extract money from pockets of the unfortunate suitors. Forms, the pretenses for which have been long exploded, are pertinaciously adhered to … and while this is the case, legal proceedings will remain characterised by an uncertainty of result, a loss of time, and a ruinous expense, which should induce every one to learn as effectually as possible to guard against a seduction into its labyrinths, or, if entangled in them, to make the most easy and expeditious escape.

“The strong tradition that each American should be able to master the laws probably peaked in the years between Andrew Jackson’s inauguration in 1825 and Abraham Lincoln’s death in 1865. Most states enforced few if any restrictions on non-lawyers appearing in court on behalf of others–as Lincoln himself did before he talked a judge into granting him attorney status.

Given America’s long tradition of discouraging lawyers, it’s surprising that in the 20th century the legal profession so successfully sold Americans on its favorite public relations slogan, “A man who represents himself has a fool for a client.” And it’s even more surprising that without great opposition, the American Bar Association convinced states to pass “unauthorized practice of law” statutes in the 1920s and 1930s, which effectively gave lawyers a monopoly over the sale of legal information.

It is less surprising–at least to everyone who isn’t an attorney–that in the last two decades many Americans–battered women, small businesspeople, landlords, inventors and disenfranchised fathers, to mention just a few–have begun to assert their historical and constitutional right to participate in the legal decisions that affect their lives.

Unfortunately, the Bar–despite the fact that its leaders concede that at least 100 million Americans can’t afford lawyers–continues to resist this powerful democratic trend. The fact that lawyers won’t voluntarily relinquish their legal monopoly goes far to explain why the profession is ridiculed by so many Americans.